Contributed by Jakob Dück, Global Industry Segment Manager at HARTING Electric

One of the most significant challenges in today’s manufacturing technology is the question: How do I serve the “very special and unusual” wishes of end consumers? As things stand today, this would appear to apply only to the end consumer worlds. But the current trend towards factoring in individual customer wishes entails consequences that extend deep into production technology. The scope and degree of Individualization as is currently strived for, can no longer be achieved with the tool kit of conventional mass production, and calls for a completely different design of production processes, including machines and systems. The individualization of mass production is one of the core aspects of Industry 4.0. The resulting challenge for the manufacturers of production systems (OEMs) is as follows: How should the necessary equipment and how should the processes for “individualized production” be shaped and designed so that the costs will not explode and the resources required will not rise sky high?

KUKA, the leading robot manufacturer, has formulated a conclusive answer: “The key [to mass customization] lies in a high degree of standardization and automation, which at the same time affords scope for variations of customer-relevant product features. What’s more, the concept of modularization, which provides customers specific, tailored product configurations based on a modular building block system, is a cost-effective way to meet individual customer needs …” [1]

This results in three central perspectives for OEMs:

- The shift towards individualized serial customization

- Modularization as the key, in combination with automation and standardization

- Preservation of latitudes for the variation of customer-specific product features

This perfectly describes the conflicting demands made on OEMs in the mechanical and plant engineering sector. The dilemma is very reminiscent of the statement ascribed to the philosopher Hegel: “Freedom is the insight of necessity.”

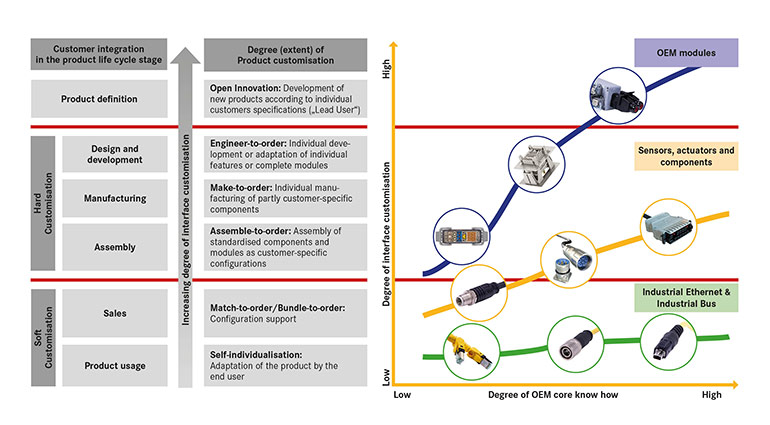

![Graph 1: OEM individualisation concepts according to time of customer integration ([2] left side) and typical design for individualised interfaces according to functional groups (right side)](https://www.connectortips.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/harting-individualized-connector-technologies.jpg)

This will be further differentiated in the following, because in some instances standardized interfaces and in others “individualized” interfaces will be more advantageous. HARTING commands many years of in-depth experience in this area, based on the production of industrial interfaces and close cooperation with customers from various industrial sectors. Practical recommendations and experience can be derived from these strengths.

The importance of customer-specific product definitions for OEMs in the mechanical and plant engineering sector can be well illustrated by the following system [2] (Figure 1 / left-hand side). The possible degree of product individualisation by the end user is related to the life cycle of production systems. The further the cycle progresses, the smaller is the remaining scope for individualisation (transition from “hard” to “soft customization”).

In order for OEMs to determine the right degree of individualization for their machines and to bring them into line with the different automation and modularization requirements along the life cycle, it is expedient to think in terms of different “clusters” or functional groups.

Sensor and actuator technology: The development of electronic components has enabled a tremendous compression of functions. Higher energy efficiency and greater packing densities go hand in hand with these ongoing developments. The technology boost in this cluster is encountered in many places in the production system: in the process-integrated acquisition of input parameters and signals, in the on-site pre-processing of this input data, in the energy-efficient triggering and control of actuators, in brilliant image processing and reproduction, as well as in the touch functionalities of the operating units. On the one hand, this technological progress facilitates the decentralization, modularization, and the scaling of machines. On the other hand, thinking in terms of ever more compact building blocks and elementary functions is becoming necessary, and the initial input and efforts required to develop such systems is on the rise.

In spite of these partially negative implications, the advantages of customer-oriented individualization of the product range in mechanical engineering outweigh the disadvantages. This is due to the fact that the appropriate overall arrangement of sensors, actuators, and other machine control components, as well as the interconnection of the functions and processes based on them, are absolute OEM domains. They alone hold comprehensive system competence here. These are the key assets they can leverage to their advantage.

Drive technology: There are similar significant and far-reaching shifts here. While know-how was at the core of mechanical development in the past, in recent decades it has migrated almost entirely to software departments or electrical design. Due to the enormous increase in performance of the technologies for electronic drive controls matched with decreasing prices at the same time, entirely new concepts for machine and production plants have emerged. The function group for the complex control of the motion sequences and related processes also forms a central competence of machine manufacturers.

Specialized Technology Units: It is noticeable that the manufacturers of manufacturing systems are increasingly concentrating on a few technologies in their development activities. The generalist perspective remains with the overall system suppliers, whose know-how resides precisely in the application and connection of technologies. With regard to the question of the right interfaces, however, it is precisely the highly specialized technology units that are of interest. A common, defining aspect of these functional groups is the fact that they are deployed as finished units or aggregates with firmly circumscribed physical and technical functions and precisely defined interfaces. The linking of the units represents the central OEM know-how, not the components used themselves.

Digitalization This term is omnipresent in today’s technical literature and other media and comprises many aspects, but applied to interfaces in mechanical engineering, it refers to data transmission technologies. Data transmission in the form of industrial bus systems and as Industrial Ethernet has long been shaped and used by the players in manufacturing technology. The possibilities of cost-effective data connection to higher-level systems up to the cloud with ever greater data throughput and real-time capabilities, however, are genuinely revolutionary in technology terms. These technologies would enable OEMs active in the mechanical and plant engineering sector to reshape their entire business approaches: Different manifestations of these changes are described and designed under the heading of Industrial IoT. All data transmission aspects, including industrial buses and industrial Ethernet, are considered here from the perspective of interfaces as a functional group or functional layer. While the solutions in this area are not part of the OEM’s core competence, they hold the greatest potential for change in today’s manufacturing systems.

HARTING offers solutions for all electromechanical interfaces required in modern control, drive, HMI, and communication technology for production systems at work in all branches of industry. Based on the analysis of customer applications already realized to date, the following advice for the individualised interfaces of the above-described function groups is derived (see diagram 1, right side).

- Generally speaking, it makes sense to use individualized or customer-specific electromechanical interfaces for the functional groups, which largely represent the core OEM know-how.

- Customer specific, tailored interfaces are most often used for those modules and aggregates that are developed or manufactured directly by the respective manufacturer. This applies to all degrees of product individualization in mechanical engineering – from “soft customization” through the various stages of “hard customization” to one-of-a-kind productions.

- With regard to sensors and actuators, the typical interfaces for the respective industry sector are usually opted for. Trendsetters and innovators, however, do try to set themselves apart from the market by deploying specific, tailor-made interfaces.

- When it comes to data interfaces, machine manufacturers rely entirely on standardized solutions. This applies both to the industrial bus and Ethernet connections employed and to all other forms of digital data transmission.

What are the main reasons behind this design of the interfaces?

In terms of data transmission, it is evident that both Industrial Ethernet and bus systems in the manufacturing area and the higher-level data interfaces are subject to tremendous change. The technologies deployed are largely determined by the suppliers of the control components. Therefore, the recommendation for production system OEMs is as :

- As far as possible, these interfaces should follow the latest standards of the control technology employed and ensure the modularity and scalability of the machines and systems.

- With regard to interfaces beyond the machine edge – e.g. for connection to higher-level systems – the interfaces should always represent the advanced state-of-the-art. Consequently, as an OEM, an economically and technically optimally designed system for current requirements is in place; a system that is at least in part capable of meeting future (as yet unknown) requirements. Moreover, company will then also be ideally equipped for the continuous expansion of after-sales and service activities based on digital services.

With regard to other functional groups, the advantages and disadvantages of individualised interfaces should be systematically weighed and listed individually. What are the arguments in favour of customized interfaces and what are the arguments against them? There are HARTING customers who have deliberately opted for non-standard interfaces on their technology units, modules, and machines. Here are the key reasons:

- There are end user requirements who operate specific production lines and want to consciously differentiate themselves from individual suppliers or focus on them;

- Differentiation vis-à-vis competitors in the expansion of business models to offer after-sales, service and similar services aimed at a long overall life cycle of production systems. Individualized interfaces allow these services to be controlled and expanded in a user-friendly manner;

- Intentionally non-standard design of machine interfaces or equipping technology with specific interfaces in order to stand out from the competition. In particular, OEMs that perceive themselves as technology leaders, innovators or trendsetters are taking advantage of these opportunities.

- Use of sensors/actuators or their combination developed according to specific specifications of individual manufacturers: In these instances, too, the protection of one’s own know-how is the strongest motive for leveraging individualised interfaces.

What individualization options does HARTING offer for customising electromechanical interfaces in order to meet even the most unusual OEM requests for interfaces in the mechanical engineering sector? In the following, the customer-specific design potentials are listed according to their increasing degree of individualisation:

- Thanks to the modular design principle of HARTING connector products, most contact inserts can be combined with different housing types. This results in convenient scalability with regard to the required IP protection class, EMC protection or the installation situation – whether in the device, as a docking solution, in the housing, on the housing wall, in the machine or cable duct, as well as indoors or outdoors;

- Cable entries and imprints on housings can be freely configured and custom ordered via online configurators;

- As many product families offer the possibility of customer-side placement with contacts with different characteristics, existing contact inserts can be designed customer-specifically; as an additional variant partial assembly should be mentioned – thereby achieving higher voltages;

- The contact inserts of most standard connectors can be provided at individual locations with coding pins instead of contacts;

- Instead of fixing screws, pin and socket combinations can be used which have a coding function, these can also be provided with special heads;

- Also with regard to data transmission, where standardization places great emphasis on the transmission characteristics of the entire interconnections and routes at work, there are options for the customer-specific design of interfaces. By means of standardized preLink contact blocks at the respective end of the data line, suitable connector types for different ends of the data lines can be realized in terms of the respective protection types required. In this way, sub-routes can be designed that are precisely tailored to the end-user environment;

- In the case of modular connector systems, contact inserts for signals, data, electrical currents, and other media such as pneumatics or fiber optics can be combined into one single connector. Based on the multitude of existing modules, an almost infinite number of different combinations can be created — representing de facto unique specimens;

- Customer specified products specified by the customer that are assembled and individually tested by HARTING at the factory, from connector sets to complete cable assemblies;

- At the highest level of “hard customization,” customer-specific interfaces are developed to meet individual customer requirements – with the aim of meeting even the most “unusual” customer wishes in mechanical and plant engineering!

Footnotes:

[1] https://www.kuka.com/de-de/future-production/sfpl/megatrends/individualisierung (EN) ; (For reference only EN https://www.kuka.com/en-se/future-production/sfpl/megatrends/customisation (EN))

[2] Piller, F. T.; Stotko, C. M. (HRSG.): Mass customisation and customer integration. Düsseldorf: Symposium 2003.

Harting Electric

www.harting.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.